My body is my journal and my tattoos are my story.

Johnny Depp

The trip on the Lemro River was interesting but it did feel good to get out and stretch my legs. The path to the village where the ladies with the tattoos lived was flooded with bright mid-day light and soon I was wishing I was back on my plastic chair in the boat. The trees at the end of the path gave welcome shade.

From the river, the village looked deserted but, as in most of Asia in the middle of the day, the villagers were sequestered in any shady spot. Even the children were staying out of the noontime sun.

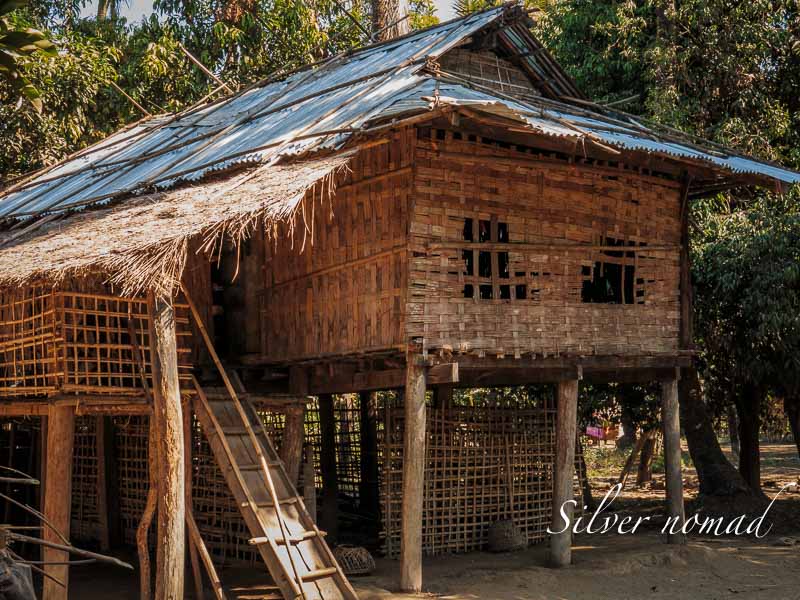

Walking into the villages is like stepping back in time. There was no evidence of any of the conveniences of the modern world that we take for granted.

The houses, on stilts so air can circulate below and also provide shade, were all made by hand and of local material. They seemed to be made of mats woven from palm leaves. Much of life is lived out-of-doors, usually under the house for that’s where it is cooler.

Some kind of Chin telegraph had announced our arrival for the ladies were busy at their looms or displaying their wares. The traditional craft of weaving has endured and there were lots of pieces on sale.

I had been a bit nervous thinking about taking photos of their tattooed faces and desperately wanted some close-up shots. The light in Asia is nearly always a problem, especially at high noon. It is an additional problem when the contrast between the light areas and the dark are intense. Most cameras, even very good digital cameras, have a problem when the dynamic range is too large: bright highlights are easily blown with washed out colours and details are lost in the dark areas.

But I need not have worried: the ladies were gracious. They were quite happy to pose and, as I got more confident, I asked them to move into better light and so there would be a better background. One even closed her eyes and motioned me to take a photo of the design on her eyelids. She was so sweet that I did as she asked but with an internal shudder. All I could think about was how painful that must have been.

Girls were tattooed at about the age of nine. Whether this was a puberty rite or a cosmetic treatment, I don’t know. It was done with sharp thorns from a plant and the ink was a mixture often involving soot. A woman in the child’s family, often the grandmother, did the tattooing.

I thought the women all looked extremely handsome and that the tattoos (lines before their time) hid the inevitable ravages of Old Father Time. Showing their tattoos, along with selling their weaving, has become an income generator for them.

The Burmese government outlawed tattooing in 1960 so nowadays young girls content themselves with applying circular patterns with thanaka. Thanaka, made from the bark of a tree, is a much less painful option. The bark is powdered and made into a paste, which is yellow. Women, men and children use it as a sunscreen.

In the next post, I write about schooling in the Chin villages so you will see photographs of many more children.

Privacy Policy

Janet, as always a very interesting and informative blog. I enjoyed reading it; wonderful marriage of images to factual information. Keep these blogs coming!

Hi Janet,thoroughly enjoyed these latest blogs. Found the information and photos fascinating. Looking forward to more.

Mgt.

Lovely to see you’re still enjoying your travels and explorations.